Tracy K.P. Gregg, University at Buffalo

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

How do astronauts go to the bathroom in space? – Henry D., age 7, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Whether you use a hole in the ground or a fancy gold-plated toilet, on Earth, gravity pulls your waste down and away from you. For astronauts, “doing their duty” is a bit more complicated. Without gravity, any loose drops or dribbles could float out of the toilet. That’s not good for astronauts’ health, nor for the sensitive equipment inside the space station.

I study volcanoes on other planets, and I’m interested in how people can work in extreme environments like space.

So how do you go to the bathroom in space or on the International Space Station? Carefully – and with suction.

A bathroom vacuum

In 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space. His trip was supposed to be short, so there was no plan for pee. But the launch was delayed for over three hours after Shepard climbed into the rocket. Eventually, he asked if he could exit the rocket to pee. Instead of wasting more time, mission control concluded that Shepard could safely pee inside his spacesuit. The first American in space went up in damp underwear.

Fortunately, there’s a toilet on the space station these days. The original toilet was designed in 2000 for men and was difficult for women to use: You had to pee while standing up. To poop, astronauts used thigh straps to sit on the small toilet and to keep a tight seal between their bottoms and the toilet seat. It didn’t work very well and was hard to keep clean.

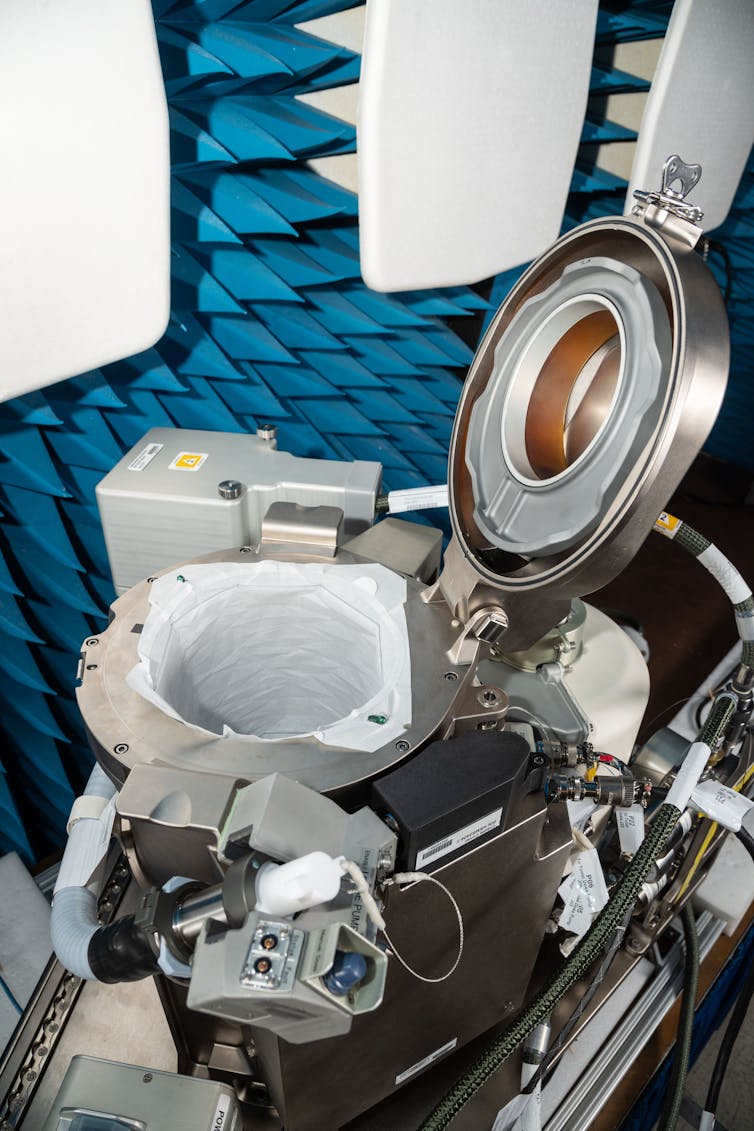

So in 2018, NASA spent US$23 million on a new and improved toilet for astronauts on the International Space Station. To get around the problems of zero-gravity bathroom breaks, the new toilet is a specially designed vacuum toilet. There are two parts: a hose with a funnel at the end for peeing and a small raised toilet seat for pooping.

The bathroom is full of handholds and footholds so that astronauts don’t drift off in the middle of their business. To pee, they can sit or stand and then hold the funnel and hose tightly against their skin so that nothing leaks out. To poop, astronauts lift the toilet lid and sit on the seat – just like here on Earth. But this toilet starts suctioning as soon as the lid is lifted to prevent things from drifting away – and to control the stink. To make sure that there is a tight fit between the toilet seat and the astronauts’ behinds, the toilet seat is smaller than the one in your house.

After the deed is done

Pee is more than 90% water. Since water is heavy and takes up a lot of space, it is better to recycle pee rather than bring up clean water from Earth. All astronaut pee is collected and turned back into clean, drinkable water. Astronauts say that “Today’s coffee is tomorrow’s coffee!”

Sometimes, astronaut poop is brought back to Earth for scientists to study, but most of the time, bathroom waste – including poop – is burned. Poop is vacuumed into garbage bags which are put into airtight containers. Astronauts also put toilet paper, wipes and gloves – gloves help keep everything clean – in the containers too. The containers are then loaded into a cargo ship that brought supplies to the space station, and this ship is launched at Earth and burns up in Earth’s upper atmosphere.

If you’ve ever seen a shooting star, it might have been a meteorite burning up in Earth’s atmosphere – or it might have been flaming astronaut poo. And the next time you have to pee or poop, be thankful that you’re doing it with gravity’s help.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Tracy K.P. Gregg, Associate Professor of Geology, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.