Dolf Gielen, Colorado School of Mines and Morgan Bazilian, Colorado School of Mines

Much of the news coming out of the U.N. climate conference has focused on the spectacle, and how countries’ pledges aren’t on track to prevent dangerous climate change. But behind the scenes, there is reason for hope.

In many countries, the energy transition is already underway as falling costs make renewable energy ubiquitous and more affordable than fossil fuels. A growing number of world leaders agreed at the climate summit to reduce methane emissions and aim for net-zero emissions.

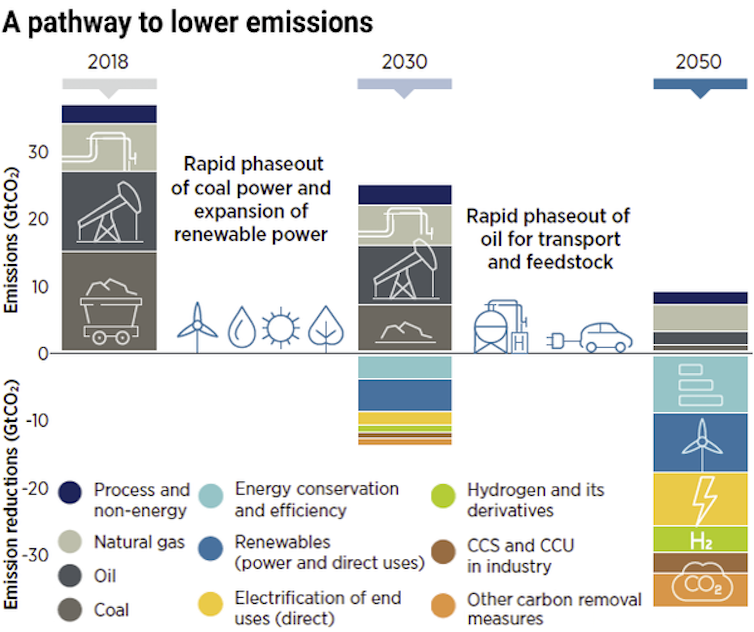

The challenge for government officials now is figuring out how to help scale up clean energy dramatically while reducing fossil fuel emissions, and still meeting the rapidly growing energy demands of billions of people in developing and emerging economies. With an ongoing energy crisis creating shortages and record-high prices in several countries, navigating this early stage of the energy transition requires thoughtful policies and well-prioritized plans.

As climate policy experts with decades of experience in international energy policy, we identified six strategic priorities that could help countries navigate this tricky terrain.

1) Deploy carbon pricing and markets more widely

Only a few countries, states and regions currently have a carbon price that is high enough to push polluters to cut their emissions.

A price on carbon, often created through a tax or carbon market system, captures the cost of harms caused by greenhouse gas emissions that companies don’t currently pay for, such as climate change, damage to crops and rising health care costs. It is particularly critical for power production and energy-intensive industries.

One goal of the Glasgow negotiations is to write rules to help carbon markets function well and transparently. That’s essential for effectively meeting the many net-zero climate goals that have been announced by countries from Japan and South Korea to the U.S., China and those in the European Union. It includes rules on the use of carbon offsets, which allow individuals or companies to invest in projects elsewhere to offset their own emissions. Carbon offsets are currently highly contentious and not delivering trustworthy emissions credits.

2) Focus attention on the hard-to-decarbonize sectors

Shipping, road freight and industries like aluminum, cement and steel are all difficult places for cutting emissions, in part because they don’t yet have tested, affordable replacements for fossil fuels. While there are some innovative ideas, competitiveness concerns – such as companies moving production out of the country to avoid regulations – have been a key barrier to progress.

Europe is trying to overcome this barrier by establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which would tax imports of goods that didn’t face the same level of carbon taxes at home.

The United States and the European Union also announced at the summit that they would work to negotiate a global agreement to reduce the high emissions in steel production.

3) Get China and other emerging economies on board

It is clear that coal, the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, needs to be phased out fast, and doing so is critical to both the U.N.‘s energy and climate agendas. Given that more than half of global coal is consumed in China, its actions stand out, although other emerging economies such as India, Indonesia and Vietnam are also critical.

This will not be easy. Notably half of the Chinese coal plants are less than a decade old, a fraction of a coal plant’s typical life span. China has raised its climate commitments, including pledging to reach net-zero emissions by 2060 and agreeing to end financing of coal power plants in other countries, but its current pathway will not yield substantial reductions this decade.

A major announcement by India’s prime minister at the COP around a net-zero goal for his country by 2070, with interim targets for ratcheting down emissions before then, is an early win.

4) Focus on innovation

Support for innovation has brought cutting-edge renewable power and electric vehicles much faster than anticipated. More is possible. For example, offshore wind, geothermal, carbon capture and green hydrogen are new developments that can make a big difference in years to come.

At the climate conference, a coalition of world leaders launched what they call the “Breakthrough Agenda” – a framework for bringing governments and businesses together to collaborate on clean energy and technology. The Glasgow Breakthroughs include making electric vehicles the affordable norm, bringing down clean energy costs, scaling up hydrogen energy storage and getting steel production to near-zero emissions, all by 2030.

The countries and companies that lead in developing these new technologies will reap economic benefits, including jobs and economic growth. More opportunities exist in market design, social acceptance, equity, regulatory frameworks and business models. Energy systems are deeply interconnected to social issues, so changing them will be successful only if the solutions look beyond the technology to societal needs.

5) Prioritize green financing

Over 160 banks and investment groups are involved in another coalition that has agreed to put pressure on high-emissions industries by tying lending decisions to the goal of global net-zero emissions by 2050.

Ramping up green financing will require transparent taxonomies, or guidelines, for defining green and clean investments; science-based transition plans for companies and financial institutions; and a hard look at portfolios of financial institutions given the risk of substantial stranded fossil fuel assets, such as coal power plants that haven’t reached the end of their life spans but can no longer be used.

Meeting the transition funding needs of developing economies should be a high priority.

6) Reduce short-lived greenhouse gases

The Biden administration announced a sweeping set of rules on Nov. 2, 2021, for reducing emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas many times more potent than carbon dioxide that comes from leaking oil and gas infrastructure, coal mines, agriculture and landfills. Methane doesn’t stay in the atmosphere as long, so stopping emissions can have faster climate benefits while carbon emissions are reduced.

The U.S. and the European Union also launched a new global pledge to cut methane emissions by nearly one-third by 2030. Over 100 countries have signed on.

This type of coalition, based on a tightly focused issue, can bring meaningful emissions reductions in places that are less likely to support broader climate agreements.

Not one solution

It is likely that U.N. energy and climate deliberations will continue to move in fits and starts. The real work needs to take place at a more practical implementation level, such as in states, provinces and municipalities.

If there is one thing we have learned, it is that mitigating climate change will be a long slog. While it’s uncontested that the benefits of greenhouse gas mitigation far exceed the costs, politicians need to show that the many energy transitions emerging are good for economies and communities, and can create long-lasting jobs and tax revenue.

This story is part of The Conversation’s coverage of COP26, the Glasgow climate conference, by experts from around the world.

Amid a rising tide of climate news and stories, The Conversation is here to clear the air and make sure you get information you can trust. Read more of our U.S. and global coverage.

This article was updated Nov. 3, 2021, with over 100 countries signing onto the methane pledge.

Dolf Gielen, Director for Technology and Innovation at the International Renewable Energy Agency and Payne Institute Fellow, Colorado School of Mines and Morgan Bazilian, Professor of Public Policy and Director, Payne Institute, Colorado School of Mines

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.