Sam Harris, author of numerous bestselling books and the host of the Making Sense podcast (formerly the Waking Up podcast), is no stranger to deep or difficult topics. In fact, he built an advertiser-free podcasting model in order to discuss ideas openly, without fear of losing sponsors. Often focusing his energy on exploring consciousness, ethics, and artificial intelligence, he recently ventured into a new type of conversation with the launch of the Waking Up Course app, a series of guided meditations and lessons focused on mindfulness.

In this exclusive full-length interview, we discuss social media’s impact on our minds, our potentially haphazard approach to AI, Sam’s new Waking Up Course app, and, surprisingly, how the practice of Brazilian Jujitsu is more real than other forms of martial arts.

Innovation & Tech Today: You’ve built a career on having deep and difficult conversations, whether that be via your books or your podcast. Social media is another way to have a public conversations, but while it’s useful for getting your message out, it’s often a driver of hyperbole and outrage. What do you think a healthier social media would look like?

Sam Harris: Well, I think in virtually every case anonymity is a bad idea. I understand the need for it in certain cases, like with whistle blowers or dissidents who would have their lives threatened if it were known who they were, but generally speaking, I think anonymity is almost entirely a toxic influence on our public conversation. So the fact that on Twitter and YouTube you really don’t know who anyone is, I think largely accounts for how vile the comments can be.

And I’ve noticed, for instance, if you select in Twitter that you just want to hear from people who have verified email addresses, I’ve noticed that cuts down immensely on the craziness that I see coming back at me. So that’s one very easy lever to pull and if all the platforms did it, I think it would improve the conversation immensely. Beyond that, we have a psychological problem with how people engage these media, and it is somewhat analogous to road rage, which is this paradoxical fact about the human mind.

In the case of road rage, if you put someone in a car and just have them interact with other people in cars, they are often plunged into states of mind and into patterns of reactivity that would never be available to them if they were walking around on the street.

It’s like the level of outrage, the kinds of things they’ll say and even do while in the imaginary safety of their car, it becomes its own form of mental illness, and there’s something about being behind the keyboard on social media that selects for a similar level of overreaction where they lose sight of the fact that they’re dealing with other human beings who are actually going to read the products of their typing. So it allows the inner maniac to come out in a way that simply wouldn’t come out in conversation with other people, certainly not face to face conversations.

So we have to learn to notice what this deeply unnatural circumstance is pulling out of us and I think we need to remind ourselves that there’s a person on the other side of the thing you’re typing and they’re about to read it when you hit send. Making that more vivid does change people’s behavior.

I&T Today: In other words, we need to be mindful of others. How do you think mindfulness connects to ethics?

SH: Well, traditionally in a Buddhist context, the connection is very direct. I think it does go in both directions empirically, it seems, which is to say that living ethically is viewed as a real support for one’s meditation practice. If you’re spending your days lying, cheating, stealing, and killing, you don’t have the kind of life that allows for equanimity and any kind of profound focus.

And so you just need to simplify your life and your relationships and ethics is what does that. Treating people well naturally causes them to treat you well, and your practice in that context can draw further energy from your desire to just be a better person in relationships.

What’s the whole point of learning to meditate and be happier? Well, it’s not merely this selfish pursuit; it is a way of dealing with all of the limitations on your wellbeing you discover in relationship to others. It’s an antidote to your pettiness and enviousness and just mediocrity in relationships, even in relationships with the people you claim to love.

So the desire to be a better person is intrinsically an ethical and pro-social one, but then there’s also the fact that the kinds of insights one has in meditation do feed back into one’s behavior in the world in that you become more sensitive to your actual motives in situations and you can become less committed to motives that are antisocial.

You can erode your attachment to yourself through meditation. All of the conventional selfish motives that would get expressed in the world – your grandiosity, your egocentricity, your arrogance, your grasping at pleasure, and your fear of what’s unpleasant – all of that stuff can get relaxed as well, and that becomes a very durable basis for improving one’s ethics.

I&T Today: This seems to get at one of the biggest issues we’re facing with social media. It’s my understanding that social media taps into the part of your brain that rewards you with dopamine when you win socially or you do something well socially, and then it deprives you of that good feeling when you do something that is socially negative. Do you think that meditation is a way to kind of break out of that cycle? It’s kind of like a drug to help wean yourself off of that back and forth or that obsession.

SH: Yeah, well it can be. There are two ways in which meditation can change your relationship to experience. One is frankly somewhat drug-like in the sense that you become more concentrated in meditation. That becomes intrinsically, pleasurably, so you have changes in state which you associate with meditation as a practice, and these are so pleasant and you become attached to them. You want to feel that way more of the time and you engage meditation as a way of changing the contents of consciousness in that way.

But that’s not really … that’s kind of a trap. Right? That’s not really the goal of meditation, or at least this type of meditation. The deeper effect is to change your relationship to experience itself in each moment and to become more accepting of the fact of ceaseless change in the contents of consciousness.

So the recognition, the thing you have been so desirous of and now finally have, is going to, it’s a pleasant taste. You’ve been wanting ice cream for the last two hours. Now you finally got it in hand and now it’s in your mouth and you’re tasting it.

To become sensitive to the time course of that whole enterprise to notice at each moment this pleasant experience is falling away. It’s intrinsically insubstantial and the more, the deeper that lesson gets ingrained, the less you’re captivated by the fulfillment of any specific desire. You’re not as held hostage as you have tended to be by seeking to change your experience in pleasant ways, and so it has this quality, the more you do it, of equalizing experience because the pleasure you’re taking in life becomes more and more of enjoying a kind of equanimity in the face of whatever is happening rather than be buffeted around by the highs and the lows and just seek to stay closer to the highs more of the time.

Essentially you’re enjoying already being happy before anything happens, before things change, before the ice cream actually arrives, and that is a far more fundamental basis for being happy in the world because things are always changing and you can’t hold on to a moment’s experience for a moment longer than it lasts. So it really entails a kind of insight into the character of all experience that allows you to shift your response to it.

I&T Today: Thinking about mindfulness and technological innovations, humans often don’t take a mindful approach to disruptive technologies. We tend to release a technology, realize the issues it’s created, and then figure out how to clean up the mess later. A great example of that, I think, is how speed limits were invented 30 years after cars became popular. Similarly, AI is a huge leap forward, but it can spread worldwide instantly. Is it too powerful of a tool to popularize now and regulate later?

SH: Well, as it gets more and more powerful, I think the regulation has to be in step with the growth and its power. Superhuman intelligence can’t be regulated after the fact. We have to get the cadence of our having conversation about the possible downside of what we’re doing to more closely track the curve of innovation and after the fact just doesn’t work when your technology is more powerful than you are.

So at some point we have to get that right. We don’t yet have superhuman AI or even human AI, but what we do have are these narrow AI projects that get regulated or reacted to long after they’re launched, and that’s at some point going to have to flip.

I&T Today: But since AI is in its infancy, as you said, what do you think the AIs that are available today could do if they go unchecked?

SH: Well, I’m not worried about what’s available today spontaneously becoming more powerful than we understand or anticipated. I think we, the people who are doing the work, will one day bring us general intelligence. I think we’re almost certainly aware that they’re doing this work, and it won’t be a matter of some narrow AI suddenly becoming general in its capacity…

I think what has to happen is that the people, the groups that are doing the work that could conceivably bring us general intelligence, they need to have some clear landmarks along their development pathway that would cause them to stop and reflect on where all this is going.

Like what capacity could a computer demonstrate in the lab at Google that would force, and should force, Google to call a meeting with everyone else who is doing this work, all their competitors, and in a moment of transparency say, “Okay, this is what we just achieved. We need to think about the implications and what can go wrong if we flip this switch.”

And I don’t know, frankly, if that’s top of mind for anyone to do at this point. I think what we more likely have is an arms race where people are just trying to advance the technology as quickly as possible before anyone else advances it more quickly than they do, and that’s obviously not incentivizing any kind of truly cautious path forward.

People at this point just don’t see any real need to worry about caution because we seem so far away from any of these potentially scary breakthroughs, but we really have no idea how long it will take us to make breakthroughs that fundamentally change the game.

I&T Today: Yeah, that makes sense. You know there was a recent story about Amazon pulling an algorithm that they were using for serving up resumes to sift through resumes. Based on the 10 years of data they fed the algorithm, it determined that women and women who went to women’s colleges were not good candidates based on the data. So even with a simple algorithm there can be negative real world impacts.

SH: Yeah, well those are the near term concerns about automation and AI which, yeah, it’s very easy to see how, depending on what data these systems are fed, we could get results which we don’t like the look of, which may in certain cases be no less true, but they’re politically insufferable. So it’s like you wind up with an algorithm that looks racist or sexist, but it could actually just be tracking valid data within it’s purview, and the answer in fact could be sexist or racist, but it’s not the answer we like.

But there are just no guarantees what you’re gonna get when you just start analyzing data in this way and you could find things which seem at minimum, to perpetuate some social injustice that you don’t wanna perpetuate. So yeah, we do have to understand what we’re getting and there are cases where, because some of these machine learning algorithm operate like black-boxes, we may not even know that we’re implementing – in this case, a sexist or racist algorithm. Because we’re not actually tracking, in that case, the effects of what we’re doing. It’s just spitting out good resumes and it’s not telling us that there’s a sexist filter.

I&T Today: Right. Let’s linger on AI for one more bit and then I want to talk about your app. People often conjure up doomsday scenarios when thinking about AI, but it’s already doing some good. What are some of the most important challenges you think we should be using AI to solve?

SH: Well, I think there are some isolated cases which have been much talked about and celebrated, and I think we really do want AI to solve these problems for us. Self driving cars is perhaps the most obvious example, and that’s just a fact that people are bad at driving cars.

We’ve been bad ever since we started driving cars. We’ve looked like we’re going to be bad forever and the moment robots are better than we are, we should be letting the robots drive, and that’s just because it should be intolerable to us that, year after year in the United States, tens of thousand of people are dying despite the fact that we’re making our best efforts not to kill one another while driving.

There are many cases of that sort of thing. I think if you look at the prevalence of medical errors, people get the wrong drugs in hospitals because of doctor or nursing errors. Anyway we can use automation or AI to prevent the predictable errors of the inattention of apes like ourselves, that’s just something we should do and we shouldn’t be sentimental about replacing that human labor with automation because real lives hang in the balance. It’s just something like a hundred thousand people die every year from hospital errors. Any way in which AI could solve for that is something we want.

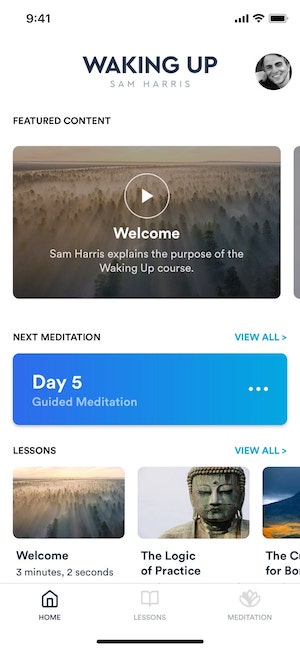

I&T Today: Let’s jump into your app. You recently launched the Waking Up Course – a series of guided meditations and lessons designed to encourage mindfulness. You said you’re uniquely qualified for this role. Why is that?

SH: Well, it’s just I have spent a lot of time both practicing meditation and thinking about the human mind in the context of science. My background’s in neuro-science, and in philosophy, but I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about the downside of religious dogmatism and sectarianism. So that diagram selects for a few unique things because there are many people who are in the mindfulness business who are teaching people mindfulness but they’re either teaching it in a fairly superficial and perfunctory way as just a tool to mitigate stress and optimize a person’s performance. In that context, it’s really taken out of the more profound insights that you get through mindfulness in a traditionally Buddhist context.

But then the people who do teach the more profound aspect of the practice almost invariably do it in a Buddhist and quasi-religious context. Those people are in the religion business and don’t understand why we need to get out. So there are not many people who understand how powerful these techniques are and understand what there is to realize and how transformative it can be personally and in terms of one’s world view, and yet understand that these deeper insights really have to be talked about in universal human terms. In terms of what we’re coming to understand about the nature of the human mind, that don’t draw any energy from this history of religious sectarianism and dogmatism and magical thinking and superstition and other-worldliness that still really drives the conversation in any traditional context.

So in terms of bringing science and philosophical rigor and secularism to this practice while honoring it as a truly profoundly transformative technology, where it is not superficial, it is not analogous to an executive stress ball. It’s far more like the large hadron collider in that it is allowing for a kind of experiment to be performed that really can change everything for a person. There are very few people, to my eye, doing that, and that’s what I’m attempting to do.

I&T Today: I see. Do you think that it’s at all ironic that when most people think about practicing mindfulness they think about separating or disconnecting themselves from technology, but you built an app to help them practice it?

SH: Yeah, but it’s a happy irony and it’s very conscious that I’m wanting to give people a way to use their smartphones, which are these agents of distraction and fragmentation in their lives, that is the antithesis of distraction and fragmentation. It just a happy fact that the smartphone can be used this way.

Most of what we do on it is a way of not connecting to our immediate experience, abstracting ourself away from it, of avoiding boredom and everything else that is arising in the present moment and seeming to limit our feeling of satisfaction and we’re looking for some kind of distraction.

It’s just a happy accident that the smartphone can be used very differently if you use it for this.

I&T Today: As I was looking through the app, I noticed that the lessons and meditations you include are surprisingly short, often around 10 minutes. So what cognitive changes would you expect from someone who meditates only 10 minutes a day?

SH: Well, I think that the move from zero to something, and something could even be less than 10 minutes, is very significant. It’s not that you get all the gains that one would get if one were on retreat meditating 14 hours a day, but there’s just an enormous difference between never doing it and doing it regularly, even for very short periods of time. So that’s, realistically speaking, just given how people are living and what they’re seeking to introduce by using an app, I think short meditations and short lessons are the best way to present it.

And further iterations to the app, I think we will allow for selecting for longer periods of time. If you want to sit for 20 minutes or 30 minutes or even an hour, there’ll be a way to do that and still get guidance. But I think it can be very powerful, arguably even more useful to repeat the practice many times for short periods rather than committing to one longer period in an given day.

So if someone said well, which would be better, to sit for one hour every morning or sit for 10 minutes, six times a day. I would expect 10 minutes six times day to actually be better, to give a better result for people. So it’s sort of in harmony with that as well.

I&T Today: Well it seems appropriate for the times too, considering how little time we seem to have in our days. Asking someone to stop and focus for an extended period is becoming a bigger and bigger ask the more connected we become.

Okay. Shifting gears. Do you have any hobbies you’d be doing if you weren’t writing books, hosting your podcast, launching apps, making TV appearances? The reason I ask is because I noticed that, in doing a Google search for Sam Harris books, ‘A Beginner’s Guide to Container Gardening’ shows up right in the middle of your list. Is that your book?

SH: Yeah, that’s not me. I haven’t noticed that, but yeah, that’s the other Sam Harris. There’s another Sam Harris who’s a Broadway show tune singer, as well, and that’s also not me.

I&T Today: Do you two get confused a lot?

SH: We have been confused a bunch, less and less. Nowadays there have just been publishing glitches where he had the bad sense to write a book at one point and his book wound up on my Amazon page as though I had authored it for a while.

But I do. Actually the one hobby I would do much more if I didn’t keep getting injured doing it is Brazilian Jujitsu. I just think it’s just the most fun, athletically, a person can have but at my age, gravity is not your friend. So I keep getting injured and having to back off and then I go back and do it once I’m healed up. Yeah, I would do that five days a week if I could get away with it.

I&T Today: Well, if you’re still doing it and getting injured, it’s definitely a passion.

SH: Yeah. I actually think it’s truly addictive if you connect with it. It does engage something in the addictive machinery of the brain where it really seems unlike almost any other athletic event. It’s really pretty fascinating.

I&T Today: Okay, I’m intrigued. Go on …

SH: It’s just something you just have to, I guess people who are not interested in martial arts might never get the point of it, but if you have any interest in that domain, there is just something about the reinforcement effect and the time course over which you learn each new technique and the fact that everything can be trained at 100% effort. I mean, most martial arts are kind of pantomime of violence where it’s never entirely clear that what you’re doing is real because, if you’re doing Krav Maga or something, you’re “practicing” poking someone in the eye.

Well, obviously you can’t really poke them in the eye and you never really know what happens if someone does get poked in the eye, and you’re engaged in this compliant exchange of techniques where you and your partner are pretending to have had a fight essentially, and that it worked out in a certain way. And none of that is what’s going on in Jujitsu.

Jujitsu is something that can be trained more or less at 100% and you see it’s effectiveness, more or less 100%. So you get into a situation where it’s absolutely clear that you would die but for the fact that the person you’re training with is deciding not to kill you, and then you’re resurrected from that circumstance and you learn what you did wrong and how not to do it again and also to do that thing to somebody else.

And each one of these lessons is imparted over a time course of like 20 minutes. So the thing that you couldn’t figure out how to stop happening to you and which then killed you in the end, and all of these things are unambiguous. I mean, you were making 100% effort not to get choked to death and you failed and it was just because the person stopped that you lived to see another day.

Then you learn to counter that thing, so it has the decisive clarity of something like chess where there’s zero luck involved. There’s absolutely no way that you will, by a hint of luck, beat a chess player who’s much better than you are and there is absolutely no way, by a hint of luck, you will beat a grappler, a Jujitsu grappler who’s better than you are.

But this is not true in all martial arts, which are no less real than Jujitsu but they’re striking based. But there is such a thing as a lucky punch. If you just get lucky and connect with somebody, you could actually knock out a professional boxer, if you actually knew how to throw a punch, and that’s just not happening in Jujitsu.

The other downside of training and striking is that you’re getting repeated head injury, so that’s no fun and so you don’t wanna train at 100% for very long. But it’s, anyway, it’s a crazily addictive thing if you care to learn about physical force and self defense on any level.

I&T Today: That’s kind of amazing. I can tell you’ve thought a lot about this, Sam. Thank you for that and for all your time today.

SH: Thank you, Dylan. Good luck with your article.

To learn more about Sam Harris, his books, his podcast, and his new meditation app, visit wakingup.com