Imagine working on a science project for an entire year, or even two. Which, considering you’re a teenager, is ten percent of your life or more. Then you head onto the world stage. Setting your project topic aside, what would that feel like? How might it impact friends? Fellow students? The world?

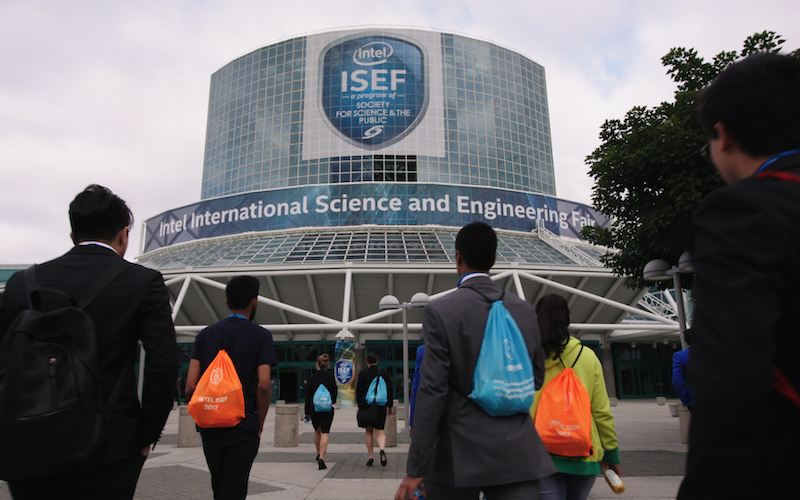

For nine boys and girls whose 2017 International Science & Engineering Fair journeys were chronicled on NatGeo’s documentary Science Fair, the impact is huge. Ryan Folz, Harsha Palagudu, Abraham Riedel-Mishaan, and Anjali Chadha stepped out of their Manual High School classroom in Louisville, KY to become role models to students globally. Myllena Braz da Silva showed her fellow Brazilians that girls can excel in science. On it goes.

Their stories form the backbone of Science Fair. The 90-minute doc swept the Best of Audience awards at 2018 Sundance and SXSW, drew large theater crowds, and was beamed into 5,000 schools nationwide. Now, as Science Fair prepares for a TV run in 170 countries, the team is reflecting on the impact. Their messages are clear: science is cool, a STEM track matters greatly, and the future is unlimited for those who pursue their passions.

Case in point: in 2008, a high school senior from the Bronx finished second in the International Science & Engineering Fair. Her name? Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“It’s so great to see such ambition and confidence,” said director Christina Costantini, herself a former International Science Fair competitor. “The greatest thing that happened was being partnered with National Geographic. The outreach they have is incredible, giving us an audience we thought we’d never reach. It’s an international film with an international cast, so we’re excited to see how it does around the world.”

Science Fair has received accolades for its personal approach, rather than a more technical, follow-the-project angle. It’s been called an “ode to the teenage science geeks on whom our future depends.” In particular, it zeroes in on the victories, defeats, and motivations of young men and women changing their lives, and the world, through science.

“At premieres, kids will come up and go, ‘Can I have a photo with you? You’re a huge inspiration,’” Ryan Folz said. “That part’s really interesting. I’m not used to people being nervous about having a photo with me! I’m just a normal person.”

Added Harsha Palagudu, one of his project work partners, “Most of the projects were portrayed pretty well, but the focus was more on our personal journeys … The focus of the film isn’t on the intricacies of everyone else’s project. They did a good job presenting what it feels like to be competing in the Fair.”

A look at the Louisville team’s Science Fair project exemplifies what it takes to stand out against the world’s smartest and most innovative young scientists. They developed a 3D-printed stethoscope with automated diagnosis algorithms. “At first, we wanted to make a cheaper stethoscope design, but then we realized we wanted it to reach doctors in countries who couldn’t even afford a basic stethoscope,” Folz explained.

Added Palagudu, “We decided to make it a fully immersive platform that included the front-end made by Ryan, easy for people with very little knowledge about technology, or science in general, to use the stethoscope. I made the algorithms that could figure out whether a heart sound was normal or abnormal, and push people to say, ‘Hey you might actually need to go to the doctor; there’s something wrong here.’”

When hearing this, consider that Palagudu, Folz, Anjali Chanda, and Abraham Riedel-Mishaan were 17 and 18 when they presented the stethoscope.

“I think our school [curriculum] helped us form the basis of the work, but once we identified our project, we learned skills and pursued them independently,” Folz added. “My brother got me an introduction to Android programming book when I was a sophomore. I learned how to make Android apps, more complex skills, then I took AP computer science classes that taught me how to code. Most of what we did utilized real-world computer skills you normally don’t get until third or fourth year of college; we had to learn on our own.”

The required focus sets young achievers apart from dreamers, as fellow teammate Chanda pointed out. “I try to make projects easy on myself, so I use two criteria when choosing: I want it to impact more people than myself; and I want it to be something that interests me so much, that when I get up in the morning, I’m excited to be working on it every day,” she said.

With the film’s more personal focus, Costantini and her production partner, Darren Foster, addressed the cultural and professional gaps between STEM-educated boys and girls, their confidence levels, and the opportunities the science world affords to each.

Chadha, a powerful and motivated young woman, minced no words. “So many young girls have reached out to me or spoken to me after showings and said this is one of the first times they really felt like there could be an even playing field,” she said. “I have to thank the filmmakers, because it’s a conscious choice to promote women’s self-confidence, equality.”

One who really feels the pressure of being a young woman in science is Myllena Braz da Silva, who lives in Brazil, where women in career fields are often stymied. “I received a lot of comments from colleagues and teachers, saying, ‘Your place is not here.’ Even my partner, Gabriel, was told, ‘Why don’t you choose a boy, instead of having a girl helping you?’ That’s the stigma – girls don’t do well as boys. I would like that to be different. I have a saying, ‘The place of the woman is where she wants to be.’”

Featured teacher Dr. Serena McCalla of Jericho High School in New York elaborated. “On these projects, boys will do very well if you let them do what they want,” she said with a chuckle. “So I step back initially, then when they have something, I tend to be tough on them to make sure it matches their vision. Once the girls find their path, they run with it. The girls in this competition do know they’re good enough. Once the girls feel they’re supported, that they’re not alone, then they will soar.”

Costantini and Foster are already thinking about a sequel, for a simple reason: the 17- and 18-year-olds in the movie are now 20 and 21, and their lives have changed greatly. “We’ve thought about a sequel five or ten years out, just to see how their lives were shaped by the Science Fair experience,” Costantini said.

You never know. A certain young Congresswoman can attest to that.